Trying to scare people into reducing their social media activity might have an opposite, unintended effect.

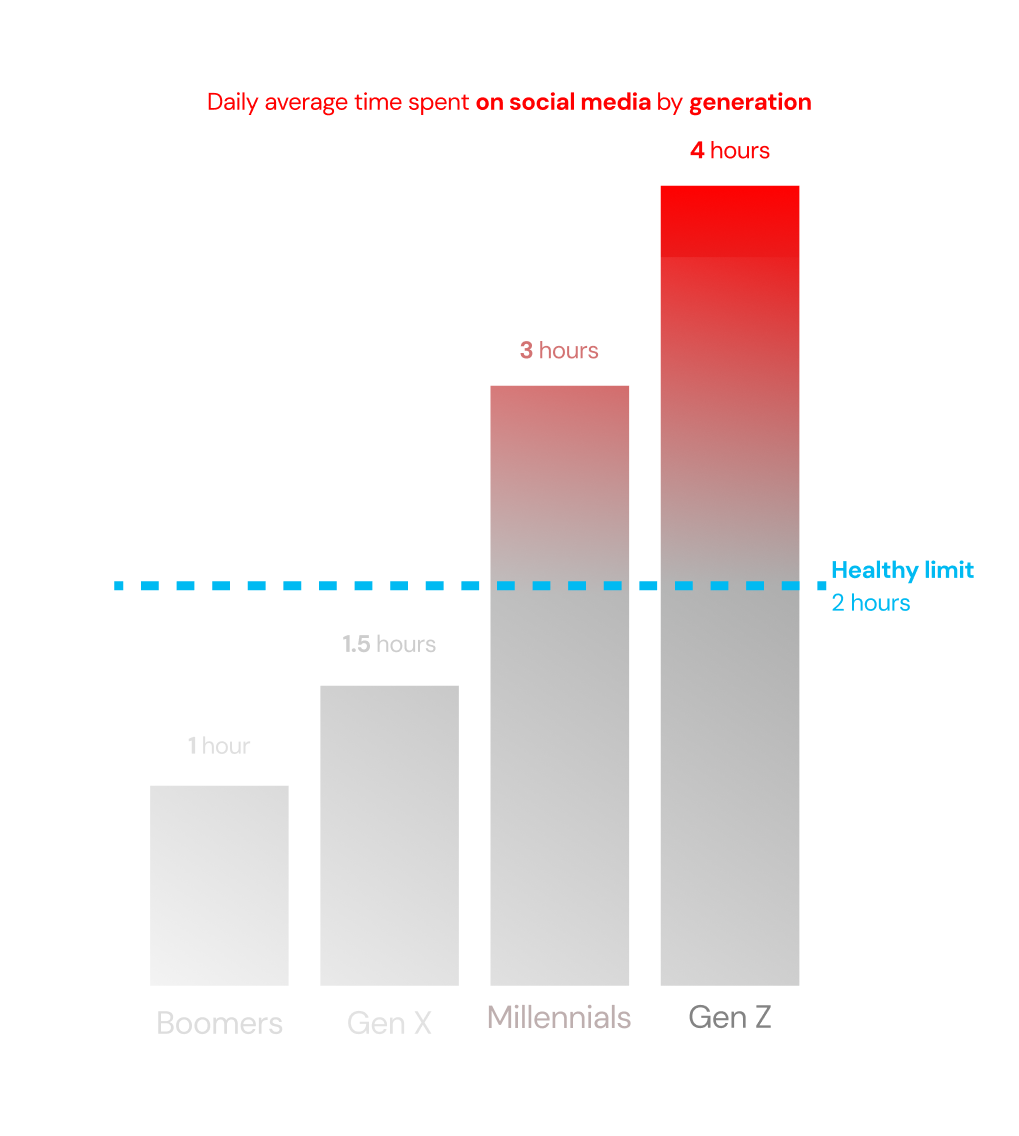

"Gen Z is spending more time than ever on social media, staring at their phones for 4 hours per day on average. That’s DOUBLE the recommended healthy amount of time. This also goes for millennials, spending 3 hours a day on average on social media."

How did that statistic you feel? Maybe a bit concerned or uneasy, but it’s likely that you’ll just forget about it entirely within the next few minutes.

This is the exact problem with scare campaigns and fear-inducing data visualisations: they don’t work against social media.

In fact, trying to scare people into reducing their social media activity might have an opposite, unintended effect.

The Privacy Paradox is not about being irrational.

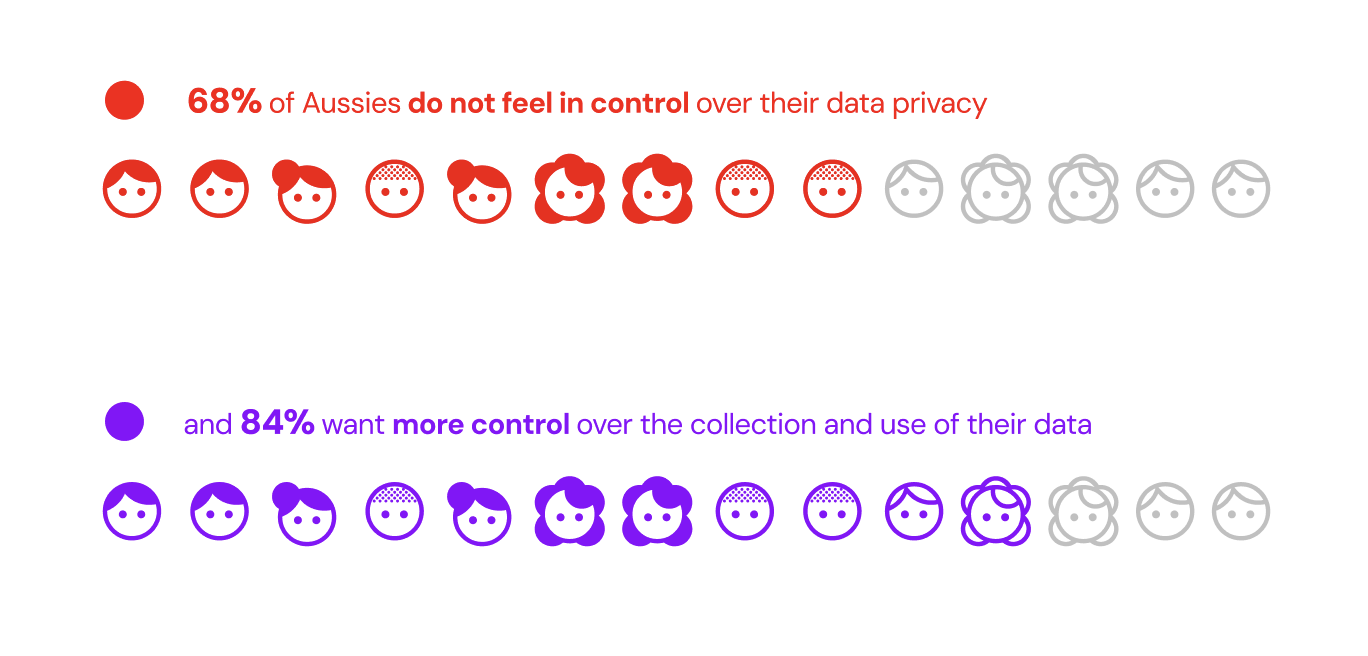

The 2019 ACCC Digital Platforms inquiry finds that while most Australians don’t agree with data collection and processing, they’ll still consent to it happening anyway. This is called the privacy paradox.

But that makes ‘most Australians’ seem ‘irrational’ and, ‘careless’ for handing over their data.

However Professor Daniel Solove (2020) shows that the privacy paradox is a misconception; handing over your data isn’t caused by irrationality – it’s caused by a fundamental problem in how our digital interactions work.

"It is a leap in logic to generalize from people’s risk decisions involving specific personal data in specific contexts to reach broader conclusions about how people value their own privacy." Solove, 2020.

Let’s use an example. You’re at a bakery, and the cashier asks for your email address. If you hand it over, you’ll get 50% discount every 5 orders. Within this context, most people would hand over their email address, due to the clear incentive and low risk. Contextually, the scenario is fine and non-problematic.

However, when you put the microscope on the data-privacy issues, you might say that we shouldn’t give our email address because the store could leak our data in a cybersecurity breach. Suddenly, handing your email becomes a careless, dangerous decision. But this is an improper generalisation.

The decision to get the discount was fine before, but as soon as you zoom into the data collection, the decision suddenly becomes problematic and ‘irrational’. The same goes for accepting privacy policies when users sign up for a platform.

Furthermore, it’s not an awareness issue either; the OAIC finds that 84% of Australians do want more control over their data.

If users feel that they have no choice but to accept what a platform does to their data, solely educating those same users about data privacy risks is ineffective.

Data privacy problems are structural, not a lack of awareness. People often don’t have a choice. That’s why scaring people doesn’t work.

Scare campaigns: they can do more harm than good

When we’re presented with "take it or leave it" propositions, where the "choice" to opt out means not using the service at all, we’re left with an unrealistic option. This is sometimes referred to as an "unconscionable contract."

We can’t do anything about it, yet we’re constantly slammed with articles and news.

This overexposure to negative news can lead to 'crisis fatigue,' a state of desensitisation and numbness that, paradoxically, can fuel behaviours like doomscrolling as individuals continue to seek out information despite feeling overwhelmed (FHEHealth, 2025).

This is because, by their very design, scare campaigns risk intensifying the very anxiety and stress that is strongly associated with doomscrolling behaviours.

So, what does a good campaign look like?

Hopefully, that’s where StopTheScroll comes in. We aim to provide more solutions than reasons to be scared.

StopTheScroll, like a good campaign, doesn’t just highlight the issue. Instead, we try our best to provide solutions.

From opting out of data sharing where possible, to explaining what a privacy policy is; take a read through some of our articles and let us know how you went!

Related content

Many Australians don't know what a privacy policy is.

36% of Australians think privacy policies stop their data from being shared. This couldn't further from the truth

How to keep your data private while your Reels, Shorts, and TikToks keep rolling

It's easier than you think: reducing the amount of data you share to platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram only takes a few clicks!